Originally written for Visual and Environmental Studies 196d (The Documentary in Latin America), taught by Professor Richard Peña at Harvard University in May 2016.

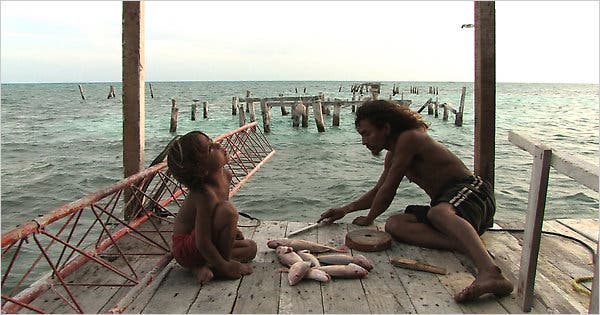

Alamar (Pedro González-Rubio, 2009) begins with a flashback sequence composed of photographs and home video that recounts the relationship between Jorge (a man of Mayan heritage) and Roberta (his Italian partner) from its beginning to its eventual end. We witness the couple embrace on the beach early in their relationship, celebrate the birth of their son Natan, and finally mourn the difference in their ways of living, which is the ostensible reason for their break-up. The union between the two people crumbles in less than four years in reality, and less than four minutes before our eyes. What was once thought to be strong and perhaps permanent ends up fading into memory. This theme of the fragility of the present is a major one throughout the film, the bulk of which follows Jorge and Natan in the last few days they have to spend with each other before Natan moves to Italy with his mother. The threat of the current state of existence giving way to a future that is less happy or wholesome constantly hangs over the film, whether it relates to the characters themselves or to the diegesis as a whole. Much as Natan is soon to lose his father, he is also nearing the end of his ability to enjoy these experiences. Similarly, environmental factors are changing man’s ability to live in community with nature in this way. Alamar evokes some sort of nostalgia for the present, even as it appears onscreen; what is captured within the frame will disappear very soon. Every object, character, and space in the film is ephemeral, and though its statements range from the political and sociological to the emotional and personal, Alamar primarily studies the phenomenon of losing what one once had.

One of the most explicit contexts in which this theme is brought up is an environmental one. As soon as the last shot of the film cuts to black, onscreen text explains that Banco Chinchorro, where Alamar takes place, is one of the largest coral reefs in the world, and that many have pushed for it to become a World Heritage Site. At first, these words are surprising; Jorge never mentions any fears he has about the future of the sea, and there are no clear signs of human intervention in the area. That the film would inform us about the possibility that the future of Banco Chinchorro could be in danger is thus unexpected, and it casts some measure of doubt on the rest of the film’s content. Nature is omnipresent within the frame for nearly the entirety of the film: even the man-made boats and aquatic structures look worn and weathered, as if humanity here is subservient to the environment, not the other way around. There is no evidence within the images that would suggest that protective measures to conserve the region would be necessary. The effect that these words have, then, is to shift our perception of the space. What felt permanent and stable now seems precarious, as if the natural health of Banco Chinchorro were in a state of decline. The footage, though clearly shot in the near-present, does not quite seem like a relic from the past, but one can imagine it soon turning into one.

That the titles that come at the end have the ability to cast doubt on the entire rest of the film is interesting. Despite the fact that nature feels untarnished throughout nearly the entirety of Alamar, the almost tacked-on environmental message puts the whole film in a different light. What this tells us is less about the fragility of nature and more about the fragility of art: our conception of the diegesis changes as soon as the credits begin to roll, due to typed words on a black screen. Many viewers are accustomed to taking whatever a film says as fact, especially if it is typed at the beginning of the credits. That these words should have a claim to truth over the image seems paradoxical, as an image (as manipulated as it may be) is ostensibly an actual record of some occurrence, especially in a work of cinematic nonfiction. There is thus an inversion of trust at the end of Alamar, one that results in our losing faith in our inferences from the image as we internalize the message from the closing title cards. (None of this is to say that the environmental message is in direct opposition to the arguments of the rest of the film, but rather that the film’s depiction of man’s relationship to nature in Banco Chinchorro is subverted, to an extent.) Of Great Events and Ordinary People (Raúl Ruiz, 1979) makes use of a similar questioning of the image in its depiction of French parliamentary elections. At one point, the image shows a bar in which people discuss politics; the narrator quickly informs the audience that a larger bar in which filming would have been more optimal banned the camera crew from working on the premises. The images included in the film, then, only tell part of the story. Alamar pushes this theme further by including a temporal axis. The images included in Alamar might tell much of the story for the present state of Banco Chinchorro, but there will come a time when they might become obsolete, the intertitles suggest. What is true now will not necessarily always be true.

Why then, if Alamar is so intent on expressing the ephemerality and vulnerability of nature, is the film sure to highlight the vibrancy and fullness of nature? At times, the images almost seem like something out of Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab, with the sonic and visual immersion into Banco Chinchorro’s environment seeming to recall Sweetgrass (Lucien Castaing-Taylor, 2009) and predict Leviathan (Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel, 2012). Like those two films, Alamar is concerned with the establishment of its diegesis as a collection of sensory encounters with a firm cultural context (and like Sweetgrass, Alamar seems to follow a historical culture in its present manifestation). Sweetgrass and Leviathan, however, express little of the ephemerality that Alamar does, and there does not seem to be a statement about the endangerment of these ways of living nearly as much. At first glance, it might seem paradoxical that Alamar would identify Banco Chinchorro as such a vivid location if the goal were to emphasize its impermanence. What this sensory development does, however, is to make the viewer understand just what will be lost if preservative measures are not implemented. Just as a film can promote sympathy for a character by explaining his psyche and pointing out his qualities, Alamar promotes sympathy for its space; Banco Chinchorro’s beauty is highlighted through serene shots of the water, scenes depicting an almost uncanny affinity between the humans and certain animals, and the tranquil white noise that is omnipresent. This sensory depiction is clearly manipulated by the filmmakers, especially sonically: cuts in the image do not always match up with cuts in the soundtrack, for example, which implies that work in post-production has been done to separate the final product from raw footage of the location. Rather than serving as an obstacle for the viewer’s immersion in the space, however, this technique has the effect of providing additional sensory cohesion. The sounds we hear when watching a particular shot might not be the exact sounds that González-Rubio and his crew heard when they were filming the shot, but they are sounds that one could hear in Banco Chinchorro, and they act to bring the viewer into the space further. By allowing the viewer to experience the environment as fully as possible, the jolt that comes at the end when the viewer realizes just how fragile it could be is all the more powerful.

Another manifestation of this theme of ephemerality relates to the intersection of European and Latin American cultures. As the child of an Italian mother and a Mexican father, Natan finds himself bridging this divide. As we learn early in the film, Natan is to spend a few days with his father in Mexico before moving with his mother to Italy. Even if there were no danger to Jorge’s way of living in an absolute sense, life in Banco Chinchorro is necessarily made fleeting by the film because much of it is told through Natan’s eyes. As he learns about Jorge’s quotidian experiences, we do; as he forms emotional bonds with nature, we do; as he mourns the drawing near of his departure to Europe, we do. There is a sort of assumed vilification of European culture inherent in Alamar: Roberta and her continent are not exactly demonized, but their influence on Natan is one of pulling him away from an environment he clearly loves. The boy’s emotions toward Italy do not matter, as even if living in Rome were Natan’s dream, this dream would pull him away from Mexico, which is cause for melancholy and nostalgia for both him and the viewer. It might be too heavy-handed of a reading to refer to this theme as one of imperialism, but there are certainly hints of industrialization and colonialism in the dynamic between Jorge/Mexico and Roberta/Italy, with Natan receiving the effects of these changes. In the end of the film, when Natan moves to Italy, the relative monochromaticity of the image reveals the difference between Jorge’s life and that of a member of a modernized civilization. Nature in Alamar’s final moments is restrained and muted, and there is less aesthetic beauty to be found in this European environment. Mexico is but a memory for the child, as we knew it would be from the beginning of the film. There is no literal imperialism here, and no European is seen to appropriate any part of Banco Chinchorro from Mexico or any of its inhabitants. There might be a sort of imperialism within Natan’s life, however, as his Mexican experiences are immediately replaced with European ones. Even if there is no apparent threat to the lifestyle that Natan experiences in a general sense, its ephemerality for Natan is clear and vital to an understanding of the film’s meaning.

Latin American nonfiction cinema is no stranger to themes of the transience of current ways of living. The Brazilian film Twenty Years Later (Eduardo Coutinho, 1984) studies how something can be depicted after it is gone, with the chief subject of the film being the two-decade period between its initial filming and its eventual completion. There are clear differences between 1960s Brazil and 1980s Brazil, but with no photographed links between these two eras, the filmmakers use interviews (filmed in the 1980s) in which the subjects explain what has happened in the meantime and otherwise show signs of the passage of time. An entire score of years is portrayed in Twenty Years Later as a gap in recorded history; the only way to depict this gap is to study its remnants. Where Twenty Years Later looks back on an absence, Alamar looks forward at one. Coutinho’s film is aware that it cannot regain lost time, so its goal is not to detail what occurred between 1964 and 1984 but rather to emphasize the fact that no detailed explanation can exist at all. Piecing together the gap would be impossible, as one can only know for certain what can be observed. Alamar allows Natan’s time with his father, which might otherwise be little more than a memory (and perhaps a gap of its own) without the making of this film, to become part of recorded history. However, even if the events that occur in the film can be saved for posterity, they are destined to become memories. Where Twenty Years Later asks how one can piece together the past, Alamar concerns itself with a piecing together of the present, constantly reminding us that it will soon be the past. The camera can only record what it sees, and by giving the camera access to Natan’s final days in Mexico, one can be sure that this transient state of being is not forgotten.

Another Latin American film that explores a similarly tangled relationship between Latin America and the more developed world is Memories of Underdevelopment (Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, 1968), a Cuban film that struggles with the question of how the poor and underdeveloped nations of Latin America could coexist with the United States and Europe. Development in Gutiérrez’s film is seen as a desirable quality that leads to prosperity and happiness; the protagonist, Sergio, constantly tries to reconcile his Europhilia and intellectualism with the fact that these interests hardly thrive in his native country. The film is more of a question mark than an exclamation point, as Gutiérrez, Sergio, and the film do not pretend to have an answer for how to transform Cuba into a developed nation. Alamar deals with this idea of development as well (albeit less explicitly), as the raw nature of Banco Chinchorro contrasts sharply with the Italian cityscape in which Roberta lives. The difference is that Alamar sees development as a cardinal sin: if Banco Chinchorro is a paradise vacation for Natan, then Italy is the home he sadly returns to. The end of the film expresses the wish that Banco Chinchorro could become a World Heritage Site and thus be preserved as a natural location free from the effects of human influence. Development, seen as something to aspire toward by Memories of Underdevelopment and films like it in the mid-20th century, is called into question here. The new way of living might be easier, more efficient, more productive, and more technologically advanced, but it would eradicate the old way of living, and that in itself is an important consideration. The ephemerality of the experiences depicted in Alamar could be caused by that very phenomenon so craved by Sergio four decades earlier. It would be pedestrian to argue that Alamar represents a return to one’s roots, as Jorge’s Mayan heritage is no secret, but it is possible for this representation of the survival of a historical lifestyle to be read in the context of films like Memories of Underdevelopment that called for modernization as a necessity for proper and fulfilling living. Even if there is nothing inherently wrong with life in Europe (Alamar never implies that there is), it is shown to inevitably be a substitute for the kind of life that Jorge lives, and that Natan experiences.

One important difference between Alamar and both Memories of Underdevelopment and Twenty Years Later is the fact that González-Rubio’s film is far more intimate and personal than the other two. Though Sergio is the only protagonist in Memories of Underdevelopment and essentially narrates the whole film, he is meant to speak for an entire country (or at least an entire country’s bourgeoisie); Twenty Years Later is character-driven as well and focuses on changes in individuals’ lives over the preceding decades, but there is something at stake beyond the lives of Teixeiras, and their experience is meant to be indicative of Brazil’s as a whole in some way. Alamar, on the other hand, is essentially told from the perspective of Natan, as it is he (and only he) who loses the experience of living in Banco Chinchorro when he moves to Europe. Even if the ideas and emotions associated with this transition in Natan’s life can relate to a more universal human experience, this extrapolation is never made explicit by the film. The processual shots that depict how one would live in Banco Chinchorro are Natan’s observations, as he is the only character present who is not used to this way of life. Thus, the viewer, who has probably not lived on the water in this manner either, aligns himself most naturally with Natan’s perspective. This alignment creates the possibility of some sort of mimetic reaction to Natan’s melancholy; because the viewer is immersed not simply into Banco Chinchorro, but into Natan’s Banco Chinchorro, the sadness Natan feels about his time with his father and the location coming to an end is echoed, to some extent, in the viewer’s reaction. The idea of ephemerality would probably not be as essential to the film if it were told from Jorge’s perspective, as Jorge will presumably continue to live in this way after his son moves to Italy.

While Natan is the narrative and thematic focus of Alamar, however, the film’s cinematographic techniques provide some distancing from the boy’s sensory and observational point of view. The characters are almost never seen to be aware of the presence of the camera or the film crew, even though several shots seem to have been taken from within inches of their faces. This contributes to the idea that we, as viewers, are intruding on something private and perhaps sacred. Were the cameraman to be addressed or made salient more often, the film might feel more candid, and the people onscreen less like characters crafted for the film. Watching the film, we might often feel as if the images are not for our eyes, as if Alamar gives the viewer access to a space and a narrative that would otherwise never have been committed to video. If the filmmakers had not made the film, the reasoning goes, these experiences (and perhaps even this entire diegesis) would have been lost: memories for Natan and Jorge, but not even that for the rest of the world. In a way, this idea evokes Lisandro Alonso’s film La libertad (2001), another piece of nonfiction cinema whose subject never visibly acknowledges the presence of the camera. At one point in Alamar, Natan is naming objects that he had seen on the trip, and he mentions the camera as one staple of the experience in a rather jarring moment of filmic self-awareness that augments the characters’ forced ignorance of the camera for the rest of the runtime; in La libertad, however, there is never any moment like this. Alonso’s languid film is almost a series of set pieces in a day in the life of Misael, an Argentine woodcutter, and though this is another personal experience that might otherwise never have been preserved in a film, there is never the same sort of immersion into Misael’s world as there is into Natan’s. Though clearly not a strictly observational film, La libertad occludes more than it reveals, and at times the context for Misael’s actions are left deliberately vague. We might be intruding on someone’s private affairs, but because little of the private information is ever shared, we feel more like rubberneckers than eavesdroppers. Because Alamar is more willing to contextualize the action and the characters, there is a greater sense of urgency; we are both more aware of the expiration date for Natan’s time with his father and more knowledgeable about the specific situation with which we are interfering.

To say that Alamar’s depiction of nature is a purely sensory or observational one would be to ignore the complex relationship that Banco Chinchorro’s fauna has with both the characters and the film itself. At one point, Jorge and Natan find a bird (quickly named Blanquita by Natan) with which they play for a couple minutes. Jorge’s natural abilities at feeding the bird and winning its trust contrast sharply from Natan’s awkward handling of the creature, but it soon becomes the closest thing to a friend that Natan has in the entire film. Perhaps because they are both young, fragile, and nervous animals, Natan is fixated on Blanquita for a few minutes. When the bird flies away, however, Natan hardly even mentions her. Blanquita, personified by the film enough that she becomes one of its few named characters, fades into memory almost as suddenly as she arrived. This is both an obvious metaphor for the relationship between Jorge and Natan and a testament to the impermanence associated with the experiences depicted in the film. That even the characters could fade out as soon as they arrive speaks to the property of time as a force that inevitably leads to the ephemerality of all things.

Cinema as a medium seems to be fundamentally linked with ephemerality. Every frame is a record of the past; the specific events depicted have occurred years ago. Even if the images themselves are destined to be identical for years to come (given proper storage and preservation), they are records of people and events that only exist in the past. When watching Alamar, there is the sense of time slipping away, but in reality, time has already slipped away. This is not to say that cinema is the only art form that can capture ephemerality, but its property of image and sound recording (in contrast to literature and drama) and its strict reliance on the passing of time (in contrast to still photography) might make it the most apt medium to depict experiences, people, and locations that would otherwise be destined to exist only in memory.

In the last shot of Alamar, Natan and Roberta are blowing soap bubbles. The camera follows a rather large bubble, and only a couple frames after the bubble bursts, the film cuts to black. This final poetic image, of something tangible disappearing without a trace, recalls the content of the film, which studies how Banco Chinchorro can be seen as ephemeral by Natan and by the public at large. The final cut to black also reflects on cinema’s property as a medium that depicts records of the past, which exist for the duration of their runtime before turning into little more than memories for the viewer. Banco Chinchorro’s future might be at risk in an absolute sense, Natan may never live there with his father again, and he has surely seen the last of Blanquita, but Alamar serves as a memorial for these times past and a marker for their passing.

References

Alamar. Dir. Pedro González-Rubio. Film Movement, 2009. Kanopy. Web. 27 Apr. 2016.

Leviathan. Dir. Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel. The Cinema Guild, 2012. Film.

La libertad. Dir. Lisandro Alonso. Fortuna Films, 2001. Film.

Memories of Underdevelopment [Memorias del subdesarrollo]. Dir. Tomás Gutiérrez Alea. Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industrias Cinematográficos, 1968. Film.

Of Great Events and Ordinary People [De grands événements et des gens ordinaires]. Dir. Raúl Ruiz. Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, 1979. VHS.

Sweetgrass. Dir. Lucien Castaing-Taylor. The Cinema Guild, 2009. Film.

Twenty Years Later [Cabra maracado para morrer]. Dir. Eduardo Coutinho. 1984. Bretz Filmes, 2014. DVD.